Elijah Burgher: Bachelors

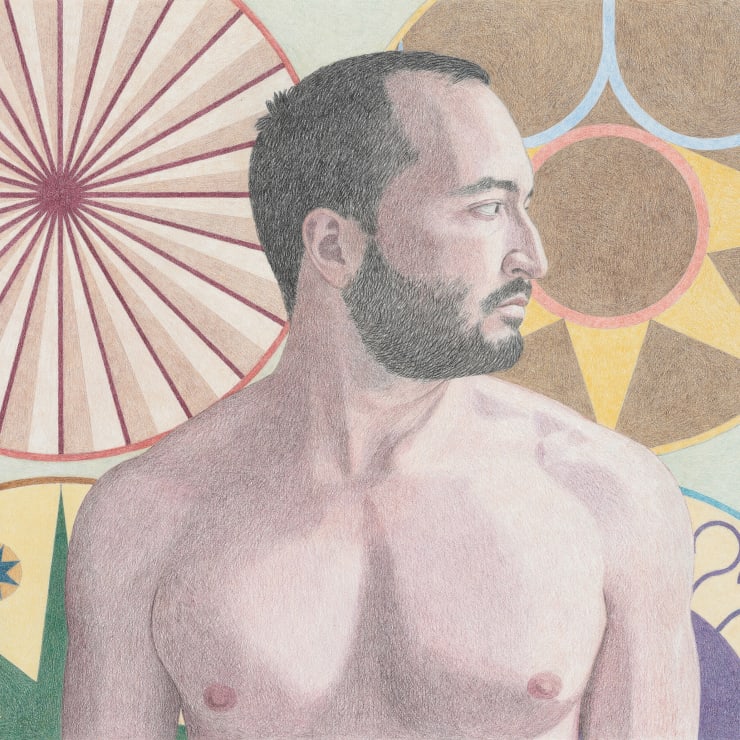

Bachelors features a series of seven colored pencil portraits, several large-scale paintings on drop cloths, and a group of unique pressure prints by Chicago-based artist Elijah Burgher. An essay entitled Gay Death Cult by Allan Doyle accompanies the exhibition.

Continuing his exploration of the intersections between desire, fantasy, and daily life, the artist employs ideas from magick and the occult to address sexuality, sub-cultural formation, and the history of abstraction. A central idea in Burgher's work is that of a "sigil" – an emblem to which magical power is imputed. By recombining the letters of a written wish into a new symbol, Burgher’s pictures, or sigils, literally encode desire while embodying it abstractly through shape, color, and composition. The resulting abstract forms combine solar, anal, mechanical and sexual elements in constellations or diagrams that serve as ritual artifacts, devotional tools, and Gnostic riddles.

This most recent series, relating to an imaginary cult alternately called Bachelors of the Dawn (BotD) and Children of the Black Sun (CotBS), focuses on portraits of the cult members and the symbols used by the cult that relate esoterically to their philosophy or world-view. The artist states; "The figure of the bachelor is crucial, embodying a refusal to marry and repeat the structures of the nuclear family and the patterns of personhood it perpetuates.

As Doyle observes: Burgher’s nudes exhibit a rigidity that seems equal parts neoclassical statue and rigor mortis. Standing or lying in hermetic spaces lit by an even, sourceless fluorescence, they do nothing. Their lack of affect heightens their physical presence. With their cool flesh, stiff comportment, and slightly averted gazes, the Bachelors appear as purely external beings, devoid of interiority. They withhold nothing. Made available to our gaze, they signal an awareness of the viewer’s presence without capitulating their self-possession. What are we to make of them? Like the sigils that surround them, the Bachelors frustrate the viewer’s interpretive instincts. Despite their display of skin, they resist appropriation for erotic fantasy.

Elijah Burgher (b. 1978, Kingston, NY) lives and works in Chicago, IL. He received a MFA from the School of the Art Institute, Chicago and a BA from Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY. He was recently a resident at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and the Fire Island Artist Residency. The artist was featured in the 2014 Whitney Biennial (selected by Anthony Elms), the 2014 Gwangju Biennial (as part of AA Bronson's "House of Shame"), The Nothing That Is at the Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh, North Carolina, and The Temptation of AA Bronson at the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, among others. His work has been discussed in the New York Times, Art in America, ArtReview, Artforum.com and was included in VITAMIN D2, the hardcover survey of contemporary drawing. The artist is also represented by Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL.

Bachelors is the artist's New York solo debut.

Gay Death Cult

by Allan P. Doyle

The adherents of the Bachelors of the Dawn share a practice rather than a dogma. Inspired by the early 20th century British artist Austin Osman Spare, the members of Elijah Burgher’s imagined cult begin by selecting a desired end or goal on which to concentrate. This wish is then encoded into conventional signs such as alphabetic characters, which are cut up and reconfigured. Reworked under extreme mental focus their inscriptions are transformed into sigils, enigmatic forms charged with psychic energy. Spare suggested that this be achieved through a variety of means, amongst the most potent of which was erotic fantasy pursued to climax. The Bachelors therefore furiously engage in a ritual recoding of inherited sign systems to the point of the annihilation of given meaning. Hieroglyphs that even their makers cannot interpret, the pictographs they construct vibrate with the anticipatory promise of desire fulfilled.

Born into what Friedrich Nietzsche calls the prison house of language, the members of the cult see signification as a primary technology of social control. Their deformation of linguistic signs is a bid for emancipation through a revisiting of the traumatic entry into symbolic life. Rather than having language imposed on them, their strategy involves a madly intense, re-enactment of the primal scene of inscription. Now, however, they hold the means of control: a pencil, a knife, a brush. The Bachelors exchange the rule-governed operations of established codes for an inscrutable private language that would speak their innermost desires. Aesthetic play renders language obsolete, but its material substratum survives disarticulation. Their impassioned rite yields new cyphers in which the form of meaning remains detectable without ever resolving into reified, consumable information. Despite their fearsome intensity, the initiates of the Dawn engage destruction as the flipside of creation in pursuit of a perverse juissance. In the artist’s hands, however, the specificity of desire that formerly fueled their attack on language is voided of any residual, personal content. The sigil ritual now becomes a means of aesthetic production rather than wish fulfillment, an allegorical machine used to submit codes and protocols to antic recombination. Burgher’s geometric forms evoke this purpose. Their multicolored shapes resemble plans for mechanisms that might have been designed to turn chains of signifiers into inoperative fragments.

In the Bachelor’s sigil drawings and paintings, the negative forms of the ground continuously interrupt the positive figures of the iconic signs. Instead of writing one letter after another they draw one on top of the other. The Bachelors alternate between additive and subtractive gestures in an improvisatory procedure both rigorous and open-ended. One shape may double another beneath it, while a third contributes a new element. The verticality of the stacks disrupts the progressive flow of language. This disordering of syntactic sequence engenders a bewildering, delirious simultaneity. The weaving of the sigils makes it impossible to localize any given sign within a single register. The Bachelors thereby engender a pleasurable slippage between top and bottom. The colored grounds found in some of the stacks increase the fragmentation brought by superimposition, presenting an even greater challenge to the icon’s demand to be read. Stacking their nonsensical signs, the Bachelors’ ludic intervention deforms the master’s voice, reversing patterns of precedence in a usurpation of parental primacy.

Burgher’s nudes exhibit a rigidity that seems equal parts neoclassical statue and rigor mortis. Standing or lying in hermetic spaces lit by an even, sourceless fluorescence, they do nothing. Their lack of affect heightens their physical presence. With their cool flesh, stiff comportment, and slightly averted gazes, the Bachelors appear as purely external beings, devoid of interiority. They withhold nothing. Made available to our gaze, they signal an awareness of the viewer’s presence without capitulating their self-possession. What are we to make of them? Like the sigils that surround them, the Bachelors frustrate the viewer’s interpretive instincts. Despite their display of skin, they resist appropriation for erotic fantasy.

Conscripting his models to his invented cult, Burgher embeds portraits of the Bachelors within fields of these enigmatic symbols. The eighteenth-century French Neoclassical theorist Quatremère de Quincy once remarked that the development of the hieroglyphic sign for the human body inaugurated the “reign of abstraction” in Western culture. Burger’s naked scribes evoke this vexed correspondence between the lived body and arbitrary sign. Members stiffen while marks move and slide, organizing themselves into clusters and dissolving again. The subtly subdued hues of the colored shapes flicker through the skin tones of the models, suggesting subcutaneous affinity between figure and ground. Paul Levack, a former student, lies prone as a set of geometric forms hovers above him, uncannily doubling his upper body. Artist and friend, Gordon Hall stands against a field consisting of a single repeated form. Bachelors drafted from across a cultural demimonde of kindred queer spirits, join them, forming a personal pantheon of interlocutors and antecedents.

Historically, the male nude was the main vehicle for the transmission of pictorial conventions and skills. It was the prime signifier in a tradition that was strictly regulated by the authority of an atelier master. Burgher rejects patrilineal lines of aesthetic inheritance and proposes a different model of artistic production and filiation. Working from digital photographs of models often posed in front of sigil paintings, his method relies upon the encryption of visual experience into inaccessible, cybernetic languages buried deep in the photographic apparatus. The camera’s algorithmic transformation of seeing into code parallels the allegorical procedure of sigil manufacture. The hierarchical distinction between master and student that formerly grounded the tradition of the male nude is now leveled. Endowed with the means of producing dematerialized, infinitely transmissible digital images, Burgher and his surrogates evade the bonds of fatherly oversight and obligation of the traditional atelier. They are sons without fathers, stealing paternal power to indulge in a wild dissemination of token meaning. The master’s workshop has become an engine of encryption, a kind of Bachelor machine.

Burgher’s works not only figure bodies and arcane symbols but also drawing itself. Historically, the medium was occluded as a means to a painted end. His tightly rendered portraits evoke preparatory drawings but occupy the ground on which painting might take place. This change may be understood in erotic terms: a flip fuck in which the former bottom practice now takes top position. Yet the eclipsed medium is still felt through its absence. Like paintings, the portrait drawings evenly fill the surface of their support from edge-to-edge. Burgher refuses the expressive language of the painterly and the extreme intentionality of his drawing echoes the Bachelors’ studied disinterest. Carefully abutting planes articulate the anatomy of the figures. For all their channeling of Dionysian energies, the Bachelor’s uninflected, cool surfaces and muted tones demonstrate an Apollonian control.

Finding ourselves amidst Burgher’s sigil works and portrait drawings the viewer becomes implicated in their operation. Like his stripped nomads, we occupy a space filled with enigmatic signifiers we cannot decode and the confusion of real and represented induces a vertiginous loss of self. Joining this imaginary sect offers a potentially transformative experience. Burgher suggests that the Bachelor’s ritualized dismemberment of signs can foster an intersubjective zone where non-appropriative relations between people are possible. This is perhaps, particularly important in our present moment when alternative models of relationality are being exchanged for more conventional, socially recognized bonds. Burgher exposes the price of designation within the heteronormative symbolic by presenting a different model of community. The Bachelors offer us the opportunity to see how much we can endure the presence of another without recourse to the appropriative violence of signification. This mode of relationality is the dawn to which the Bachelors have pledged themselves. Endlessly looping between meaning and nonsense, figure and ground, body and sign, they would enjoin us to an oscillation without end.

-

Artist Elijah Burgher Has A Magical Time

Ben Sanders, Windy City Times, Jul 14, 2015 -

Drinking the Kool-Aid with Elijah Burgher’s 'Bachelors'

Emily Colucci, Filthy Dreams, Jun 14, 2015 -

Critics’ Picks: Elijah Burgher

Joseph Akel, Artforum, Jun 1, 2015 -

15 Painters To Watch In 2015

Steven Zevitas, New American Paintings, Dec 15, 2014