Miroslav Tichý: Sun Screen

Sun Screen

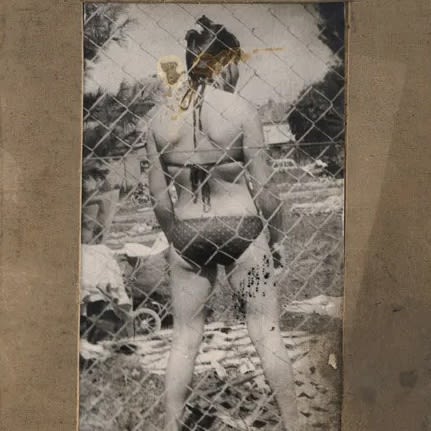

A bather stands alone behind a wire fence. She looks down, hand on hip, letting one arm dangle to her side. Her awkward stance seems both posed and natural, studied and unaware. Slowly taking in the bather, watching her emerge from wavering patches of light and shadow, one recognizes that the maker of this image seems to have rejected the conventional values of good photographic practice at every stage of production, ranging from the exposure and development to the printing and storage of the photograph. What are we to make of such a willful disregard for technical proficiency and the niceties of high art culture?

In his use of the conventional motif of the standing female nude, the photographer alludes to academic training, while conversely his uneven technique implies an untrained producer. Shot with one of his crudely modified cameras, the darkened edges that vignette the image and the bleached surfaces of the figure’s surroundings indicate under- and over-exposure of the negative. Spotted and abraded, the print appears to have been haphazardly developed and then left on the floor of the studio to be walked on, as was its maker’s habit. Despite such rough treatment, the battered print compels our attention, soliciting extended viewing in a manner that belies its amateur aesthetic. It was in fact, like all of Miroslav Tichy’s photographs, selected from amongst hundreds of shots the Czech artist took on his routine walks through his home city of Kyjov. They were then developed, printed and cropped by the artist himself. Considered, yet artless, Tichy’s photographs of bathing women evidence a paradoxical coupling of intention and accident. Products of an intentionally de-skilled rather than unskilled methodology, they testify both to the cultivated disregard typical of his mature work and to much modernist production since the mid-nineteenth century.

Tichy’s technique harkens back to the moment of photography’s birth, particularly bringing to mind the early ‘sun pictures’ of the inventor of the medium, Henry Fox Talbot. Marked by the irregularities of an experimental process, each of Talbot’s paper negative prints were a singular result of a technology that had not yet shed its alchemical origins. The preparing, exposing, bathing, washing and rinsing of the prints were as important in the making of a photograph as the opening and closing of the shutter. Tichy’s improvisational darkroom technique recovers this irreducibly material, impure origin of photography itself. Like Talbot’s salted paper prints, each Tichy photograph is a unique entity whose beauty bears witness to the vicissitudes of duration; the temporal register of his work is not that of a perfect, punctual moment but of a palimpsest of circumstance. Thus, one may argue that the photographic process itself is as much his subject as the women he pictures. Revealed to the sun, the exposed flesh of Miroslov’s bathers becomes an analog of the photochemical skin of the sensitized paper on which their features are burned.

As in many of Tichy’s images from the 1960s and 70s, the photograph of the standing bather is viewed through a fence that encloses her within a gridded pictorial field. Although its inclusion was likely due to the photographer being banned from entering the grounds of the civic pool, the motif became a key element of his compositions that resonates throughout his oeuvre. Even when no fence is visible, the regular divisions of a grid are echoed in other prints from the period, such as the striations of a stone wall that surrounds a pool into which a woman hesitantly dips her toe; or in the divisions of a railing behind which a group of children frolic; or again, in a set of blacked-out squares the artist violently imposed on the figure of a fully clothed walking woman.

In the standing bather photograph, the fence forms a cage drawn in pulsating lines of light and shadow. Two highlighted strands intersect precisely at the tip of her nose, collapsing the distance between container and contained. With this coincidence, Tichy again evokes academic practice, bringing to mind photographs that have been gridded for use as models for painters. The photographer would, on occasion, superimpose drawn lines on top of his prints in order to recover a lost contour. Academically trained as painter whose works reference Picasso and Matisse, Tichy was deeply cognizant of the modernist engagement with the grid. He was also familiar with the tradition of Renaissance perspectival projection where grids were used to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface, a system he once claimed in an interview to have taught himself prior to receiving any drawing instruction.

In the bather photographs, the grid materializes the picture plane, establishing the divide between real and represented space. It dismembers the body, rendering it into identical units. Excluding the viewer, the grid locates the motif on the far side of the picture’s surface. These bathing women are figured as objects of longing that leave artist and viewer locked in emotional isolation, always desiring from a distance. Both captive and captivating, Tichy’s enclosed figures testify to the power of the body to fascinate: we want what we cannot have. The fences, like his retrograde technical mannerisms, deny the viewer unmediated access to the motif, while enmeshing him or her in a network of power relations. From our side of the screen, we view the subject through the photographer’s viewfinder. Forced to the margins, we vicariously partake of unauthorized scopophillic activity and thereby risk subjecting ourselves to the surveillance and persecution he suffered.

For all their hints of perverse if not outright predatory behaviour, Tichy’s interest in his subjects was, as he explicitly claimed, purely pictorial. Consummation is here placed in perpetual deferral and erotic longing is channeled into the pleasures of aesthetic complication. His goal was not possession of these women’s bodies but the sustained rewards of frustrated viewing afforded by his photographs of them. For Tichy, the photograph is the Thing. Indeed, as much as they offer the delights of the flesh, the bather prints make us feel an even more primal drive: our need for delineated shape. It is our love of resolution, our eye’s hunger for contour and clarity - for form itself – that Tichy teases into a state of exquisite titillation. The eccentric photographer’s antiquated pictorialism is therefore not a product of nostalgia or a byproduct of a personal fetish, but a considered aesthetic strategy forged in the art historical and social conditions of our time. Tichy’s convoluted method subverts the current omnipresent ideology of the dematerialized image that promises the unmediated, instantaneous satisfactions of the real. By deploying a painterly vocabulary of disarticulation and accident, he reminds us of the subtle pleasures that lie in operations of the photographic medium itself, in gratification delayed. - Allan Doyle

-

Miroslav Tichý

Lauren O'Neill-Butler, Artforum, Nov 1, 2011 -

Critics' Picks: Miroslav Tichý

Britany Salsbury, Artforum, Aug 14, 2011 -

Portfolio: Miroslav Tichý

Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn, The Paris Review, Aug 8, 2011 -

The Lookout: A Weekly Guide To Shows You Won’t Want To Miss

Leigh Ann Miller, Art in America, Aug 4, 2011