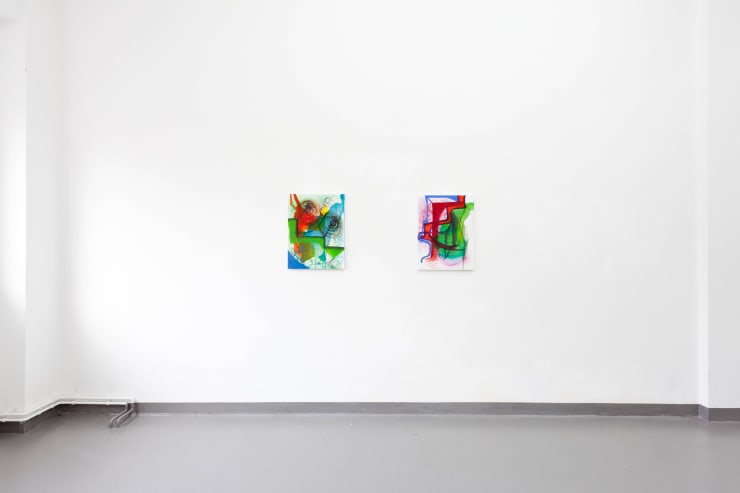

A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Philip Diggle, Joanne Greenbaum, Ryan McLaughlin & Anne Neukamp

Philip Diggle, Joanne Greenbaum, Ryan McLaughlin & Anne Neukamp

In 1997, the late American writer David Foster Wallace published a collection of essays, "A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again", that announced his arrival as a contemporary thinker of considerable moral force at a time when to do so was to essentially risk public stoning. While the topics of the essays ranged from cruise ship travel writing to the semiotic relationship between television and contemporary fiction, Wallace’s main concern, which was evidenced in the surprising intimacy and warmth of his tone, was to lessen the distance between the writer and reader that had widened since the rise and institutional embrace of Postmodern thought. In fact, such was the uniqueness of his curious tone that when he wrote of his hero, David Lynch, for instance, or about the mathematical beauty of tennis played at its highest level, it seemed like Wallace was as incapable of containing his enthusiasm and passion for his subjects as he was unwilling and uninterested to even try. In these essays, by mapping the mythic and the mundane and conjoining the academic and the everyday all in the same breath, Wallace did his best to bring an end to irony’s tyranny of ridicule, condescension, suspicion, and hostility, and to once again see irony as a literary device instead of a world-view.

When viewing the current exhibition, please consider the following remarks that Wallace made about the role of the literary artist in his essay, "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction".

"The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows."